Loqu: An Interface for Linked Data Cubes

- Published

- 2020-04-05

- Identifier

- https://alexkreidler.github.io/loqu-paper/

- Repository

- https://github.com/alexkreidler/loqu-paper/

- License

- CC BY 4.0

Abstract

Keywords

- Linked Data

- Data Cubes

- SDMX

Introduction

The amount of open data on the Internet, especially that published by governments and statistical organizations from all over the world, has grown immensely. Despite this progress, serious challenges remain in making that data accessible to users and enabling the general public to gain value from the data.

While a user who knows exactly what data they are looking for may be able to find, download, and use data quicker than ever, most other users will jump from data catalog to data catalog, downloading CSVs or other formats, and spending significant time just to explore the data.

Several unique developments have taken different approaches to solving these problems. Firstly, the Semantic Web community has advocated for the adoption of the Linked Data technology stack, which includes RDF, OWL, and SPARQL as the data, logic, and query layers [1] by data provider organizations. A limited number have adopted such technology. Many works have proposed methods to convert source data from providers into semantic data that is more valuable for users, or proposed tools to explore and visualize that data. Those will be discussed in a later section.

Secondly, many organizations have adopted Data Catalog tools, which are central repositories of datasets, often containing basic information such as the format, license, and location of the data. Some of these catalogs have recently begun to provide features to describe the structure of the data or perform basic visualization. However, the availability of such features is limited.

Thirdly, public datasets that are valuable for businesses have created an entire industry of public data providers, sometimes known as “alternative data providers.” These companies often have hundreds of employees and maintain large data processing pipelines to transform the data that is published publicly into more valuable, useful data that is easier to consume and visualize. Although some of these services make limited features available to the public, they generally require users to sign up or pay a fee if they want to export the data or create more advanced visualizations, and thus are not fully accessible.

While the latter two developments may be helpful in limited cases, they both take a centralized approach, either with the data provider adding additional visualization tools, or an aggregator providing the entire pipeline from data normalization to user interface or export. Thus, these systems result in a fragmented and complex ecosystem for users who want to consume open data.

The Semantic Web, however, offers a solution that data itself to be linked in a federated manner by design. However, a few challenges have limited Semantic Web solutions for the data exploration problem. One challenge is simply the complexity and ease of use. For example, a survey of Linked Data consumption tools [2] indicates that often, systems for consuming Linked Data are more complicated and result in a worse experience for users than tools for more common “3-star” data.

That survey also provides a valuable goal post with in-depth criteria for a Linked Data consumption tool with a broad set of features. Loqu however focuses on a subset of features that are the simplest and most valuable for users to start with.

The second challenge with existing Linked Data consumption tools is scalability, particularly for statistical data. The next sections will describe the source data for this particular application that precipitated such concerns in this project, explain in more detail the existing solutions, and briefly mentions Loqu design decisions.

The rest of the paper will describe the Loqu interface, data pipeline, and deployment model, followed by some conclusions and evaluation of future work.

DBNomics Source Data

DBNomics aggregates data from national and international statistical institutions on topics such as “population and living conditions, environment and energy, agriculture, finance, trade, etc.” [3]

DBNomics has a simple hierarchy of data composed of providers, datasets, and data series. A dataset in DBNomics is a data cube, with a set of dimensions, attributes, and measures. DBNomics includes a default dimension (Period) and measure (Value) that are handled specifically by the API. A DBNomics data series is a slice of the data cube along along every dimension except for Period.

DBNomics currently has 81 providers, over 20,000 datasets and over 700 million data series.

Due to this massive scale, it seemed infeasible to attempt to load all 700 million series, with potentially 40 observations each, into a SPARQL database. That number would exceed the largest public knowledge graph recorded.

Therefore, I chose a different approach: Loqu only stores the metadata from DBNomics in the SPARQL database.

Background and Design Decisions

These systems are often constrained by scalability and cost concerns. Such services are funded by academic institutions or individuals, and often go offline after a period of time. To minimize such risks, Loqu only stores and links dataset metadata, emphasizes the Content Delivery Network in deployment, and generally tries to do as little as possible on the server. For example, the first version of CubeViz had a dependency on a PHP server to perform many computations, although new version, CubeViz.js, has been introduced that is completely client-side.

Loqu Interface

Loqu was designed with roughly three stages: Search, Explore, and Visualize. Functionally, they help the user find and evaluate each dataset, and perhaps perform basic analysis, before exporting to another tool

From the home page, users can search, select one of the featured datasets, or browse by an entity like Countries.

Search

Firstly, Loqu provides a quick and easy search interface directly on the homepage. This autocomplete box searches datasets, and users can click a button to expand and go to the search page. This is implemented with Typesense on the backend and Algolia’s instantsearch.js library, which includes React components on the frontend. TypeSense has several attractive features. It is easy to set up, very stable, and scales fairly well. It is also popular and has a community that supports it. In the future, syncing the Virtuoso database with TypeSense may be an issue.

Explore

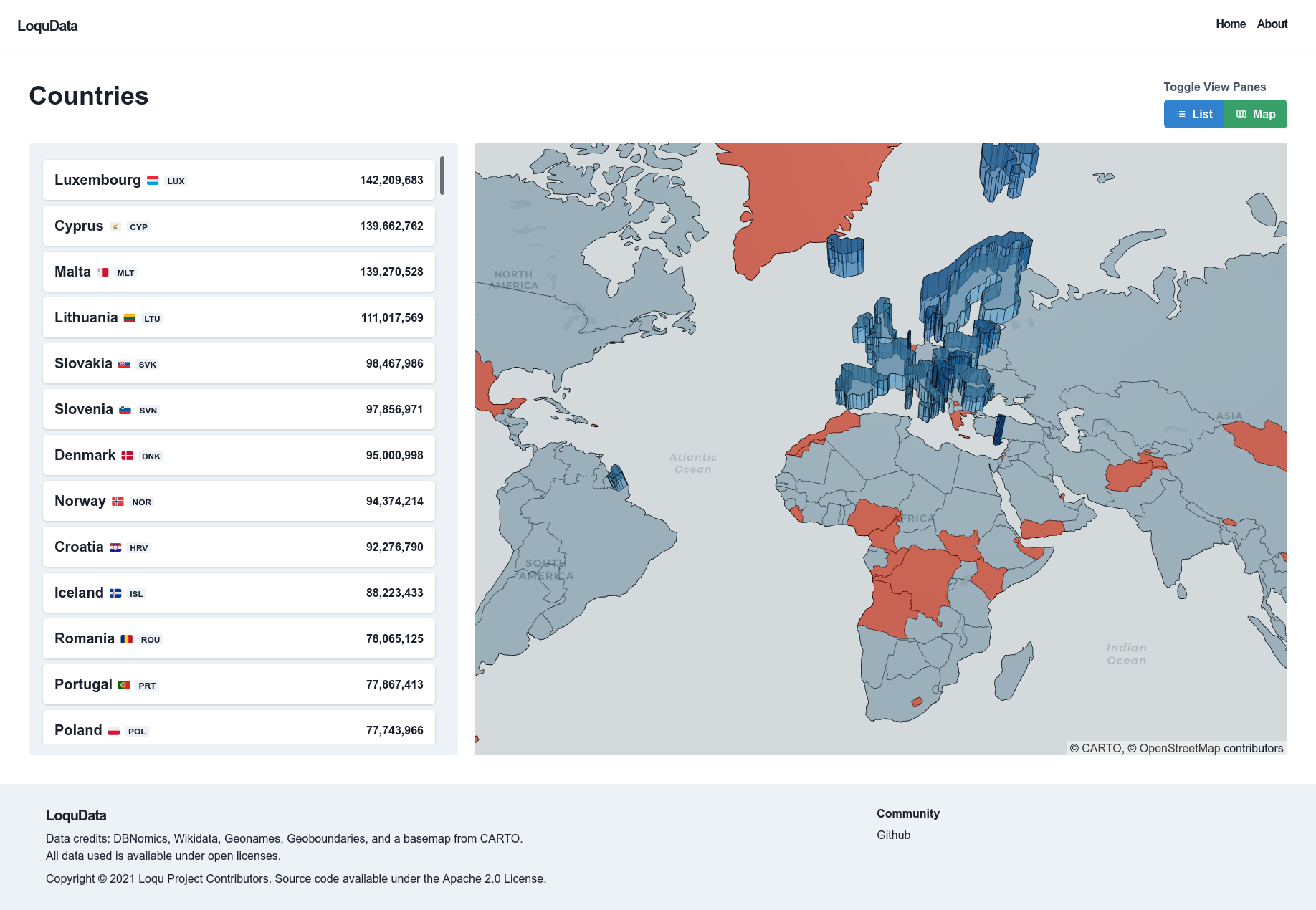

Users can also explore by linked entities. Currently the only supported option is by Country, but users could also explore by other common statistical concepts like Age, Gender, etc.

The Explore page for countries can display a list of each country with its name, flag, ISO country code, or a 2D or 3D map of the countries (using the deck.gl library). It also can show the number of datasets that are linked. Once a user has selected a country, the country details page displays pagination to show the datasets linked to that country.

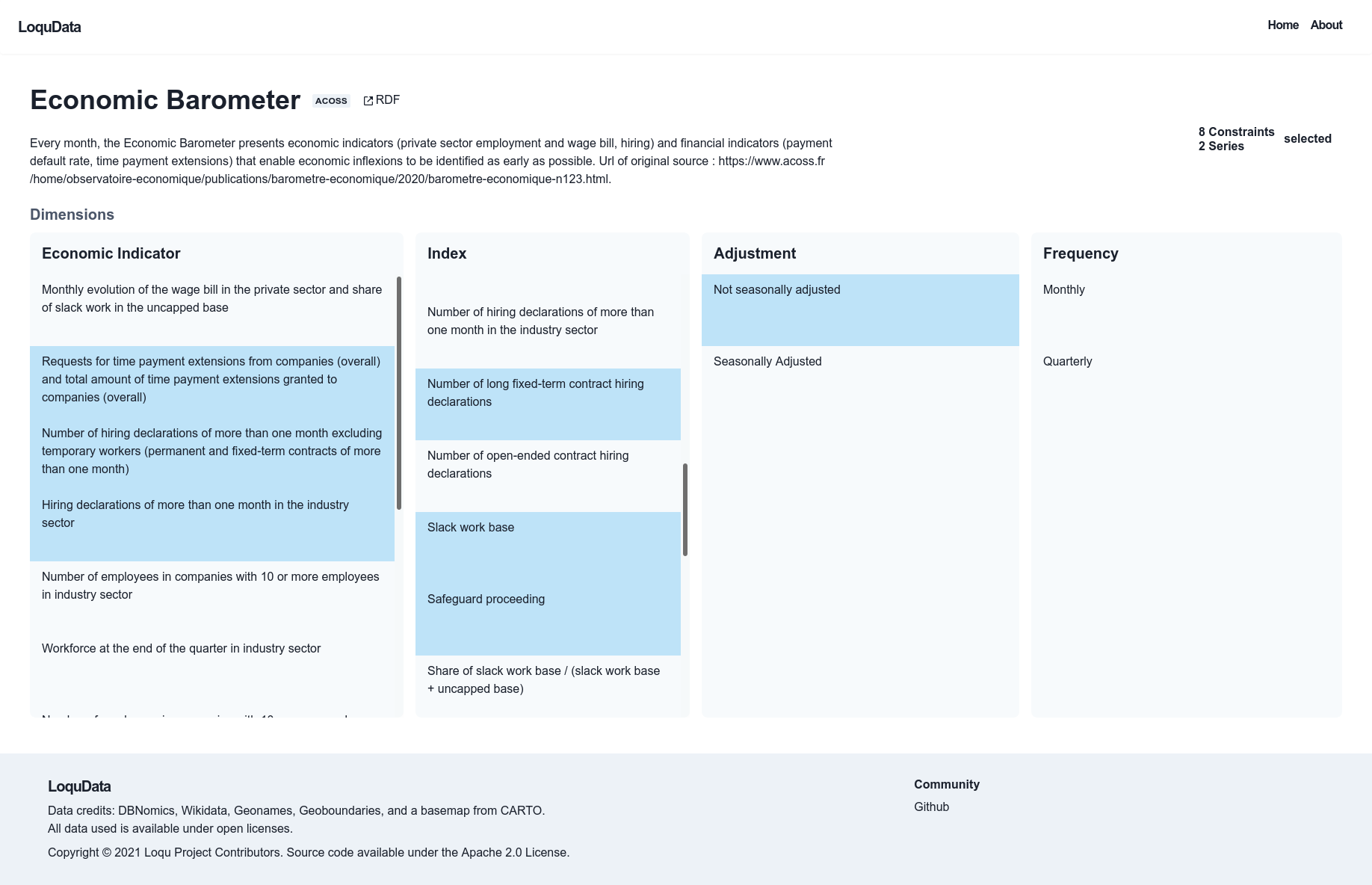

Dataset View

At this stage, Loqu only has dataset level metadata, for most series contains all the useful information a user will use to find the data cube or series. However, occasionally a series that is expected to exist as some combination of dimensions may not exist. The Dataset view sends quick API requests while the user is selecting dimensions to determine the number of series by each dimension.

Additionally, this imposes the constraint that the user must select only a specific series, and cannot perform visualizations across multiple, as is common when visualizing a data cube. This is primarily a limitation of the JSON-based API that DBNomics provides to serve the data. Written in Python, it returns data in the JSON or CSV formats. Although it allows users to query with multiple series, this is generally fairly slow, especially because it does not allow users to constrain their request on the time dimension. It does provide an option to normalize the data series, because often, one data series has more or less of the timestamp values, or NULL values in some places that make it difficult for end users to work with.

In the future I hope to work with the DBNomics team to provide exports for data in other formats that would allow in-browser data-cube visualization.

Visualize

Series

Once the user selects a single data series (from DBNomics), they can visualize it with the Series view, which simply displays the series values as a table, and an interactive time series chart. The DBNomics interface has a similar feature, but also provides the option to visualize multiple time-series in a dataset using a line chart. While this is valuable for later versions, I decided rather than rely on the DBNomics API to do this, it would be better to make the changes described in the prior section to enable this functionality and more as part of the Data Cube View.

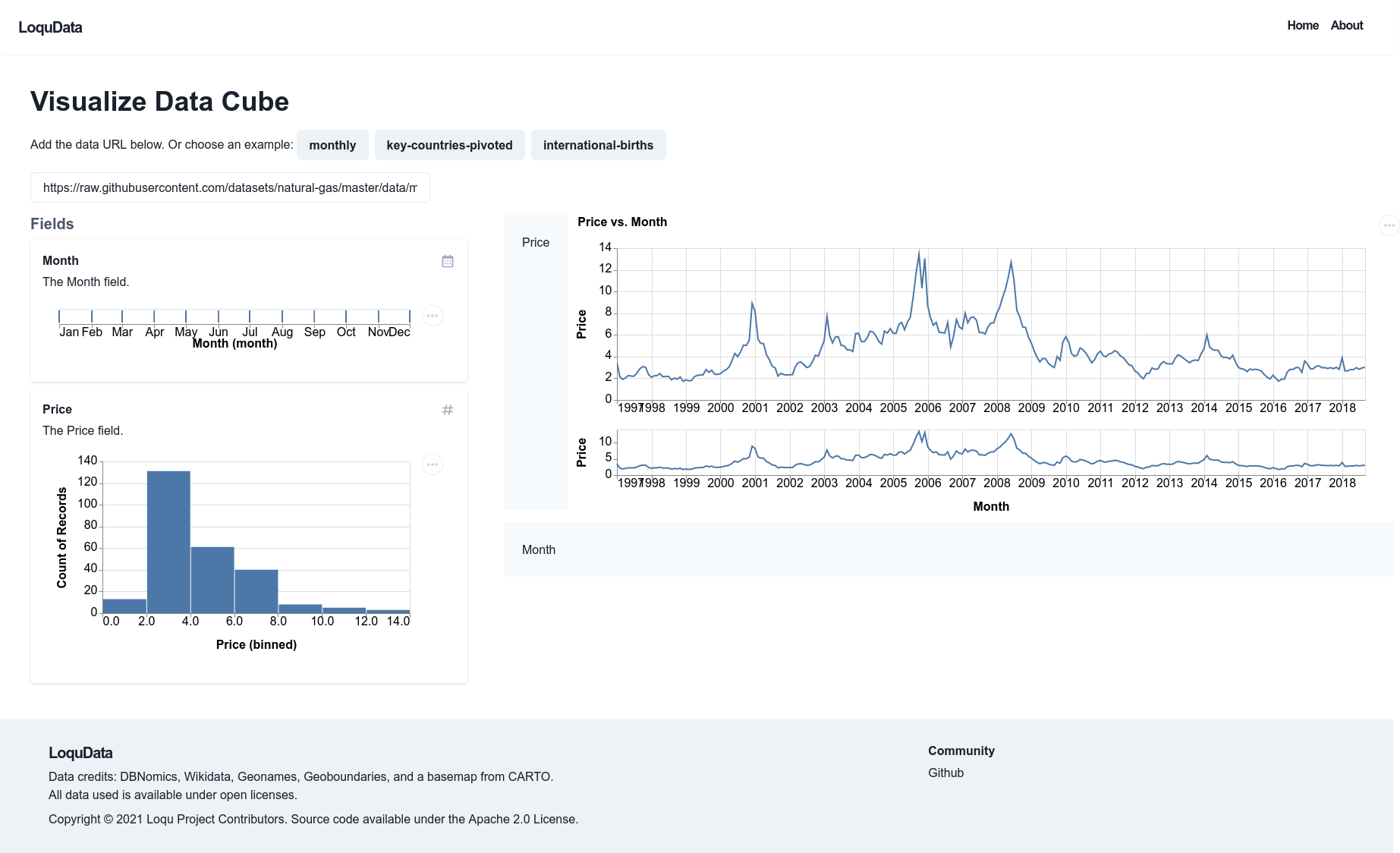

Data Cube

The Data Cube View is available when the full tabular file is available on the client. The system automatically infers basic data types like “string,” “number,” “datetime” etc. I also focused on improving the performance of this part of the platform by integrating with the Apache Arrow libraries in Rust compiled with WebAssembly, however this is not currently deployed, but will be soon.

The interface shows the “Fields” view, where each field in the table is shown as a card with a title, description, basic data type, and semantic type. Users can drag and drop data fields to change the order (for example to indicate importance) or to place them in dropzones in Dynamic Charts.

These charts are generated by passing Vega-Lite JSON specifications, [13] which provide a grammar of graphics [14] to the Vega library, through a React component. Vega includes tools for data transformation, such as binning, counts, or aggregation, encoding data to various properties, like the X and Y axes, or the color, and finally “parameters” which enable user interaction such as tooltips or the selection of elements in the graph [15]. All of this is specified in JSON, without a dependency on a specific language, and can be rendered on a client or on a server.

Notably, Vega relies heavily on a tabular data model and on traditional concepts from relational algebra. Thus, it would be a difficult task to reliably transform generic RDF into such a tabular format. However, Data Cubes with observations described by the RDF Data Cube Vocabulary (QB) are well-structured and can be verified using Integrity Constraints in the specification, so it is feasible to convert such a representation into a tabular format for visualization with Vega. However, at this stage, Loqu does not include that functionality.

Data Pipeline

DBNomics provides data in a JSON format that mimics the structure of SDMX metadata. I investigated a few tools to this data to RDF.

I evaluated YARRML (based on RML [16]) for mapping the JSON to RDF. However, its capability for linking triples created from separate parts of the JSON tree based on subjects was not very effective. Additionally, it requires the developer to specify every property that they would like to map.

In the end, I built a custom pipeline as follows:

- A Node.JS script uses the

json-transformslibrary to rearrange the JSON file and add certain properties like@idand@type, and also adds a JSON-LD context. - A Golang tool uses the goLD library to convert the JSON-LD into N-Triples.

- Because some characters (often

<>) in the IRIs are invalid, a tool scans for those invalid files and moves them to another directory. - Then, a script loads the N-Triples into Virtuoso (open source version). I tested several SPARQL databases or triple-stores, including Jena and Oxigraph, a relatively new database written in Rust. Although each database had some quirks, the primary reason for switching to Virtuoso was its faster loading time, [17, 18] which allowed for quicker iteration while building the data pipeline.

- The final step is to link the data structures to public knowledge graphs. I used the LIMES link discovery tool [19] via configuration files that mapped code list values that contained certain keywords, like

REF_AREAorgeoto Wikidata entities.

Deployment

Loqu was designed with scalable and cost-effective deployment in mind. In particular, the CDN (Content Delivery Network) is key to the deployment model. I use Cloudflare’s free plan, which allows significant bandwidth at no cost, caching of files up to 512MB, and 100,000 Cloudflare Workers (serverless function) requests per day.

The Cloudflare service routes requests to the API, search service, or static hosting providers for the frontend code or metadata.

Currently, the Virtuoso server is on a private network, and a simple Node.JS API runs SPARQL queries interpolated with certain query parameters. This both reduces risk from malicious clients, and allows for caching of frequently-accessed responses (such as the country data). In the future, I hope to make the SPARQL endpoint publicly available.

A Google Cloud Storage (GCS) bucket hosts the metadata, with about 7GB of content (the original JSON, JSON-LD and NT files).

I have also investigated using a Cloudflare worker to handle content negotiation (i.e. to return data from the static storage bucket if the request contains an Accept header with the application/n-triples MIME type, but to return the frontend code to render the interface if the header is text/html)

Conclusions

This paper proposed Loqu, a new interface for exploring and visualizing data that makes use of a Linked Data metadata model. It focuses on scalability and easy of use, and is applied to an extensive open source database of statistical data.

Loqu, which accepts data from anywhere and allows any user to semantically annotate and then visualize it, provides a serious improvement over the previous fractured system where some data providers have data exploration or visualization interfaces and others do not.

Finally, Loqu is completely open source with only open data. The source code and all transformed data use the Apache 2.0 and Open Data Commons Open Database License (ODbL) respectively.

The Loqu platform is deployed at https://loqudata.org and the code is available on Github.

Like other projects [20], I hope consistently maintain and keep Loqu available to the public, which should be feasible for several years because of its low cost.

Future Work

The survey of Linked Data consumption platforms provides many ideas for potential features. In future versions of Loqu, I hope to further build out the following functionality in subsequent versions. The service should:

- fetch source data from DBNomics in a tabular format for data-cube visualizations

- improve visualization editor by integrating a GUI form tool, and allowing users to write JSON-based Vega templates

- allow users to sign in and save visualizations

- achieve fuller compliance with the Data Cube and CSVW specs

- federate metadata as well as data so users could run their own instances of Loqu to create metadata, or use Loqu to visualize data with externally provided metadata

References

1. W3C Semantic Web Activity, https://www.w3.org/2001/12/semweb-fin/w3csw, last accessed 2021/04/17.

2. Klímek, J., Škoda, P., Nečaský, M.: Survey of tools for Linked Data consumption. SW. 10, 665–720 (2019). https://doi.org/10.3233/SW-180316.

3. About DBnomics, https://db.nomics.world/about, last accessed 2021/04/17.

4. Martin, M., Abicht, K., Stadler, C., Ngonga Ngomo, A.-C., Soru, T., Auer, S.: Cubeviz: Exploration and visualization of statistical linked data. In: Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on World Wide Web. pp. 219–222 (2015).

5. Linked Statistical Data Analysis, https://csarven.ca/linked-statistical-data-analysis, last accessed 2021/04/17.

6. Capadisli, S., Auer, S., Ngonga Ngomo, A.-C.: Linked SDMX Data: Path to high fidelity Statistical Linked Data. Semantic Web. 6, 105–112 (2015). https://doi.org/10.3233/SW-130123.

7. The RDF Data Cube Vocabulary, https://www.w3.org/TR/vocab-data-cube/, last accessed 2021/04/17.

8. UKGovLD/publishing-statistical-data, https://github.com/UKGovLD/publishing-statistical-data, last accessed 2021/04/17.

9. Ding, L., Lebo, T., Erickson, J.S., DiFranzo, D., Williams, G.T., Li, X., Michaelis, J., Graves, A., Zheng, J.G., Shangguan, Z., Flores, J., McGuinness, D.L., Hendler, J.: TWC LOGD: A Portal for Linked Open Government Data Ecosystems. Web Semantics: Science, Services and Agents on the World Wide Web. In Press, Accepted Manuscript, (2011). https://doi.org/DOI: 10.1016/j.websem.2011.06.002.

10. van der Waal, S., Węcel, K., Ermilov, I., Janev, V., Milošević, U., Wainwright, M.: Lifting open data portals to the data web. In: Linked Open Data–Creating Knowledge Out of Interlinked Data. pp. 175–195. Springer (2014).

11. Ermilov, I., Auer, S., Stadler, C.: Csv2rdf: User-driven csv to rdf mass conversion framework. In: Proceedings of the ISEM. pp. 04–06 (2013).

12. Statistical Linked Dataspaces, https://csarven.ca/statistical-linked-dataspaces##related-work, last accessed 2021/04/17.

13. Satyanarayan, A., Moritz, D., Wongsuphasawat, K., Heer, J.: Vega-lite: A grammar of interactive graphics. IEEE transactions on visualization and computer graphics. 23, 341–350 (2016).

14. Wickham, H.: A layered grammar of graphics. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics. 19, 3–28 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1198/jcgs.2009.07098.

15. Satyanarayan, A., Russell, R., Hoffswell, J., Heer, J.: Reactive vega: A streaming dataflow architecture for declarative interactive visualization. IEEE transactions on visualization and computer graphics. 22, 659–668 (2015).

16. Dimou, A., Vander Sande, M., Colpaert, P., Verborgh, R., Mannens, E., Van de Walle, R.: RML: A generic language for integrated RDF mappings of heterogeneous data. In: Ldow (2014).

17. Addlesee, A.: Comparing Linked Data Triplestores, https://medium.com/wallscope/comparing-linked-data-triplestores-ebfac8c3ad4f, last accessed 2021/04/12.

18. Atemezing, G.A., Amardeilh, F.: Benchmarking Commercial RDF Stores with Publications Office Dataset. In: Gangemi, A., Gentile, A.L., Nuzzolese, A.G., Rudolph, S., Maleshkova, M., Paulheim, H., Pan, J.Z., and Alam, M. (eds.) The Semantic Web: ESWC 2018 Satellite Events. pp. 379–394. Springer International Publishing, Cham (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-98192-5_54.

19. Ngonga Ngomo, A.-C., Sherif, M.A., Georgala, K., Hassan, M.M., Dreßler, K., Lyko, K., Obraczka, D., Soru, T.: LIMES: A Framework for Link Discovery on the Semantic Web. Künstl Intell. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13218-021-00713-x.

20. Sustainability Plan, https://github.com/comunica/comunica/wiki/Sustainability-Plan, last accessed 2021/04/17.